Exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic in the past one year, China’s relationship with the West reached a new low. The current bilateral relation between Australia and China perhaps sums it up: the worst in decades.

There has always been some animosity between China and the West, which is often attributed to their ideological differences. The emergence of a communist-led authoritarian state created some anxiety among the capitalist western democracies. US, which hails itself as the “leader of the free world”, often finds itself in direct conflict with China. (Of course, the rivalry between the two superpowers also plays a part.)

But is China really all that different from the West?

Here comes the great contradiction. Politically, China is firmly a communist state; but economically, it is capitalism in its finest (or worst) form.

The Chinese government’s unrelenting stance is that the country is “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, but the fact is that China is a capitalist country with merely a communist political system. Capitalists account for 60% of China’s GDP and provide 80% of the country’s urban jobs. That is the reality that both the Chinese government and people are aware of, even though they don’t openly admit it.

In fact, the sheer extent of China’s capitalist economy created one of the worst inequality in the world. China’s Gini coefficient stands at 0.47, compared to the US’s 0.41. (Australia’s Gini coefficient is 0.32.)

Yet, all the kids in China are inculcated with the idea that China is the socialist country that will one day become a communism utopia, where everyone will be made equal in status as well as wealth. It is written in China’s constitution that “the ultimate goal (for the country) is the realization of communism”.

I remember my primary school days back in China, we were taught that “we are the heirs of communism”. We were also taught to sing the song with those very words.

Speaking of teaching, here comes another great contradiction. The textbooks in China teach kids that the foundation of Chinese communist ideology is the rule by the proletariat – in other words, the rule by the working class. However, the reality is the rule by the “elites” – the politburo, the well-connected and the wealthy capitalists, some of whom are also communist party members. (Jack Ma, the richest person in China, is a communist party member.)

In a country where connections are so deep rooted, it is no surprise that many celebrities are Chinese parliament delegates, who meet up every year to discuss major state issues and vote on important legislation. Some of the biggest names in China, such as movie stars Jacky Chan and Stephen Chow, basketball player Yao Ming, director Chen Kaige and veteran actor Chen Daoming, are among the celebrity delegates.

In 2017’s Hurun Report, which tallies China’s richest people, it was found that the richest 209 Chinese parliament delegates were each worth more than RMB2 billion. In comparison, China’s National Bureau of Statistics reported that the median per capita disposable income of Chinese residents was RMB27,540 in 2020.

It looks like China is far off its ultimate goal after 75 years of communist rule.

Chinese history books also teach students that peasant rebellion(农民起义)is a regular occurrence throughout Chinese history and sometimes resulted in the overthrow of dynasties. Oppression by the state was always the main cause of the rebellion.

As early as the Warring Sates Period (476BC-221BC), ancient Chinese scholars were already keenly aware of this phenomenon and wrote the famous adage: “The water supporting a ship can also upset it.” (水能载舟,亦能覆舟。)It means that people can support the king, but they can also overthrow him.

That adage was passed down in history books for more than 2,000 years. I learned it from my secondary history lesson in China. Yet, descendants don’t always take heed of ancient wisdom, and history keeps repeating itself.

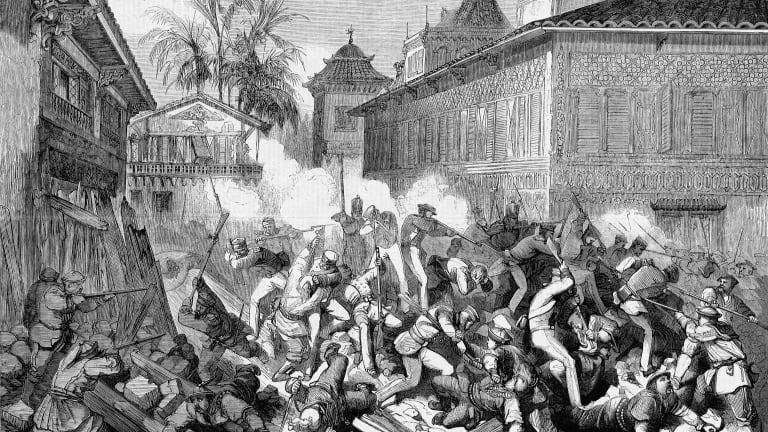

The first major peasant rebellion in China – Dazexiang Uprising – happened in 209BC and paved the way for the downfall of Qin Dynasty. Other large-scale peasant rebellions include Chimei Lulin uprising during Western Han Dynasty; The Yellow Turban Rebellion during Eastern Han Dynasty; Wagang Army Uprising during Sui Dynasty; Huang Chao Rebellion during Tang Dynasty; Red Turban Rebellion during Yuan Dynasty; The Rebellion of the Northen Shan during Ming Dynasty; and Taiping Rebellion during Qing Dynasty.

The Chinese history was also dotted with other smaller-scale rebellions.

Interestingly, when the civil war broke out between the Chinese communists and the then Kuomingtang-led regime in 1945, the peasants backed the communists. The Kuomingtang government was filled with corruption, and peasants were angry with the punishing taxes. The Chinese communists rallied the popular support of the peasants and won the civil war in 1949.

But the irony is that the Chinese peasants now have become so marginalized that they are not even recognized in their own country.

In 1958, nine years after Chinese communists came into power, the Chinese government created a unique system – Hukou (household registration system). The main purpose of Hukou is to restrict the movement of Chinese people, especially the peasants.

A Chinese citizen’s status is categorized into either urban or rural on Hukou, depending on where the person was born. Rural citizens are not allowed to settle in the city and their children cannot be admitted into urban schools. A rural person’s children are automatically assigned to rural status on Hukou.

In Australia, people from regional areas can settle in the cities freely. They can buy a house, have their children and build their family in the city, and their children can attend local schools. No one would bother to check where they are originally from. In China, its own citizens from rural areas who work in the city are openly called “migrant workers”, or “peasant workers” (农民工). They are more vulnerable and sometimes fall victim to the exploitation by their city employers.

Urban citizens have become the culprits in this biased system, me included. I was born in a large city in southern China – Changsha. Growing up in the city, everyone around me talked about migrant workers like they were not our fellow citizens – they were only in our territory temporarily. They came to work in our city for better pay and they would go home eventually. The sneering tone was common. But I was young and couldn’t grasp the underling problem. I grew up thinking that was just the way of life.

Today, when I talk to my Chinese friends who are from big cities, I can notice their sense of pride clearly. And many from China would attest to this: Beijingers and Shanghainese tend to be arrogant towards their fellow countrymen. The reason is simple. Beijing and Shanghai are the tier-one cities, which are supposedly the best in China. Their citizens were born with privileges, because they don’t need to worry about going elsewhere to find better life opportunities.

Apart from job opportunities, big cities also have better infrastructure, facilities and resources for healthcare and education. Though that’s common in other countries, China has 1.4 billion people fighting for the resources. Urban citizens have enjoyed these privileges for so long, they are unwilling to give them up.

Unfortunately for the peasants, their fate was decided when they were born. As if history was repeating itself again, peasants are bearing the brunt of an unfair system, this time created by a socialist society.

But China has thrived in the last few decades despite these obvious contradictions. None of them seems to have affected the country’s progress. And that, perhaps, is the biggest irony.